Frequently Asked Questions

-

Why did Harold leave London?

#0001 | 1st February 2025 | JBS

If Harold had stayed in London, William would eventually have been forced to return to Normandy empty handed. The only credible explanation for his decision to leave London is that he thought it would help his strategy to be in the theatre of war, and that he thought there was no risk in doing so. We will return to Harold's strategy in Questions #0003 and #0005. The only credible reason he might have thought that there was no risk entering the theatre of war is that he was unaware of the Norman cavalry. Wace says exactly this, explaining that Harold only discovered the strength of the Norman cavalry on the day before the battle. Harold and brother Gyrth immediately realised the dire consequences. See Question #0013 for how this calamity probably happened.

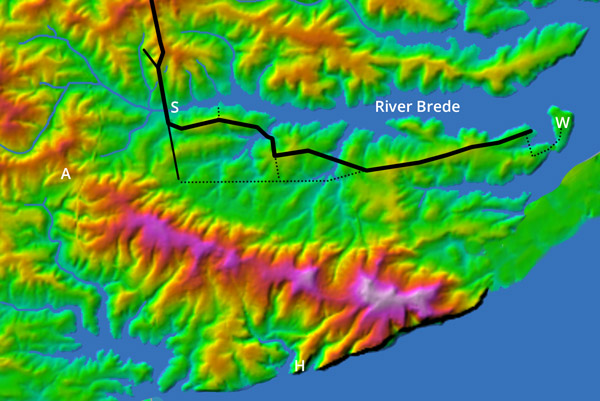

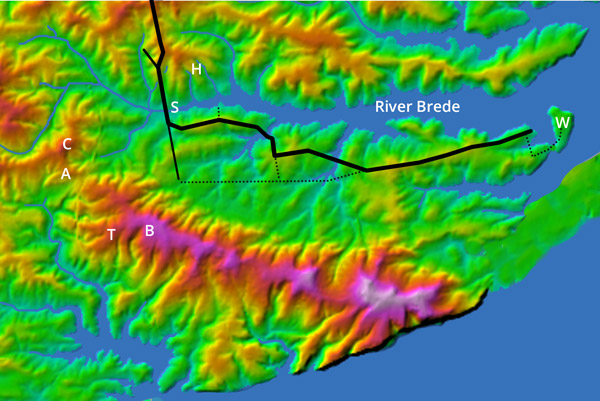

Harold's ignorance of the Norman cavalry explains all his subsequent actions. We will return to it repeatedly in the Questions below and elsewhere. With regard to why he felt safe to move from London into the theatre of war, he would have reasoned that he just needed to stay north of the Brede and close to the Roman road to be totally secure. A footbound enemy would move too slowly across fields and ridgeways to outflank him. If the Normans tried a frontal attack along the Roman road, they would have been delayed crossing the bridge over the River Brede, giving plenty of time for the English to counterattack or fall back along the Roman road to safety beyond the Rother.

This contradicts the orthodox narrative in which Harold raced down to the theatre of war because he was incensed by the Normans plundering his ancestral lands. That narrative is based on several Norman accounts that accuse Harold of being a hot-headed fool who was goaded into this rash decision. It is baseless propaganda. There is no evidence that Harold was impetuous, irascible, or gormless. Indeed, the evidence suggests the opposite. His sister says that he was smart, prudent, and widely criticised for being too attentive to advisors, while William of Jumièges, in the enemy camp, says that he was 'agreeable in his manner' and 'affable to everybody'. The orthodox narrative is awry.

#2189 | 1st February 2025 | JBS

Reply

-

Did Harold really intend a surprise attack on the Norman camp?

#0003 | 2nd February 2025 | JBS

By tradition, Harold's strategy was to assault the Norman camp in a surprise attack. It is implausible. William and Harold had been exchanging messages during Harold's journey south. Harold knew that William knew his exact location, so he would also have known that the Normans could not be taken by surprise. If the Normans could not be taken by surprise, the English stood no chance of successfully storming the heavily fortified Norman camp, so Harold would not have attacked it.

The traditional surprise attack narrative is based on some Norman accounts that specifically claim this was Harold's intention. Their chroniclers were not privvy to Harold's plan and, very probably, everyone that knew his plan died in the battle. Perhaps they deduced the surprise attack narrative themselves, or perhaps they were instructed to report it, trying to disprage Harold as a hot-headed fool.

Yet there must be a rational explanation for why Harold arrived at the theatre of war with an understrength army and then chose to camp within striking range of the enemy. Wace, a Channel-Islander, was no more likely than any of the Normam chroniclers to have known Harold's plans, but he was under no pressure to denigrate Harold and he had had a hundred years to think about it. His 'Norman cavalry intelligence failure' explanation - see Question #0001 and #0013 - is plausible and consistent with all Harold's actions. It is certainly more credible than that he was trying a surprise attack, and no other explanations are on the table.

If Wace's explanation for Harold's actions is so credible, how did the surprise attack conjecture become widely accepted? We suspect that modern translations of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle are culpable. It states: “com him togenes æt þære haran apuldran”. Modern translators interpret this to mean 'Harold came against him [William] at the hoary apple tree', thereby apparently corroborating the Norman accounts that say Harold went on the attack. It is being mistranslated. The Old English word 'togenes' almost always means 'towards' or 'to meet', with no implication of aggression. The hostile version of togenes is 'ongean' which refers to an aggressive move or an attack. It is common in Old English manuscripts, including in the very next sentence which states that William came against Harold unexpectedly. Victorian translators including Ingram and Thorpe use the correct passive meaning of togenes. We guess that modern translators have adopted a non-standard aggressive meaning of togenes to align with the orthodox engagement scenario, but it is a circular argument of errors.

#2200 | 2nd February 2025 | JBS

Reply

-

What then was Harold's strategy?

#0005 | 3rd February 2025

It has been suggested over recent times that Harold's strategy was to blockade the Normans on the Hastings Peninsula. While this is a likely softening up tactic to improve Harold's negotiating position, it seems unlikely to have been Harold's main strategy because he would have delegated brother Gyrth to implement it. Indeed, the only credible strategy that would unequivocally explain Harold's actions is that he intended to negotiate face-to-face with William.

It was standard practice in medieval times to buy off powerful invaders, thereby avoiding the vagaries of battle. The Anglo-Saxons had been buying off the Vikings for centuries. William’s messages to Harold showed a readiness to negotiate. Harold had a compelling incentive to negotiate a deal and Wace says that he sent a message to William offering a bribe: “The messenger hastened to the duke, and on the part of king Harold, told him that if he would return to his own land, and free England of his presence, he should have safe conduct for the purpose; and if money was his object, he should have as much gold and silver as should supply the wants of all his host.” The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle also implies that Harold intended to negotiate. As we explain in answer to Question #0003, it says: “com him togenes æt þære haran apuldran”, where Old English word 'togenes' almost always means 'towards' or 'to meet'. It is saying - as Ingram, Thorpe and others proposed more than a hundred years ago - that: "Harold went to meet William at haran apuldran". Even if it meant 'towards', it would be in a passive sense, meaning that Harold intended to negotiate or blockade the Hastings Peninsula.

We are convinced, not least because there are no credible alternatives, that Harold left London intending to meet William face-to-face, ostensibly to negotiate the William’s return to Normandy or the renouncement of his claim on the English crown. ‘ostensibly’ because there is a possibility that Harold intended to ambush William at the meeting place.

#2202 | 3rd February 2025 | JBS

Reply

-

Why would Harold negotiate with William, and why face-to-face?

#0007 | 4th February 2025 | JBS

Harold had nothing to lose and potentially much to gain by negotiating. If William could be bribed to renounce his claim on the English crown, Harold would win a lasting peace. If, on the other hand, Harold left the Normans to stew and they returned home empty-handed, they might have continued to press their claim on the English crown for centuries. After all, England's monarchs did not relinquish their claim on the French crown until 1802, and only did so then because it had been abolished.

William had a straightforward incentive to offer negotiations: he needed to lure Harold into the theatre of war to kill him. The only credible bait was to give the impression that he could be bought off, but only in face-to-face negotiations. While this is never said explicitly in the contemporary accounts, Wace, Carmen, Poitiers and others report that Harold and William were negotiating via messengers while Harold was in London, as well as during his journey south. William had therefore shown a readiness to negotiate and it was standard practice at the time to avoid the vagueries of battle by whenever means were available. It seems by far the most likely explanation for Harold's actions.

Harold would only have agreed to face-to-face negotiations if he felt totally secure. In his ignorance of the Norman cavalry - see Question #0013 - he would have felt safe holding face-to-face negotiations on the Roman road bridge over the River Brede, and this was probably his plan. UnfortunateIy, it was not safe from cavalry attack.

#2204 | 4th February 2025 | JBS

Reply

-

Why did Harold leave most of his army behind?

#0009 | 5th February 2025

Several Anglo-Norman accounts say that Harold left more than half his army behind. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle implies much the same by saying that a significant proportion of his men had not arrived at the time of the battle. The only rational explanation is that he believed that the force he took to the theatre of war was adequate to achieve his initial aims, and that extra men would be difficult to provision.

This latter is unquestionably true. Sub-Andredsweald East Sussex was very sparsely populated in Anglo-Saxon times with a low intensity of farming. Its livestock and grain stores would have been plundered by the Normans. Harold would need to bring provisions through the Andredsweald. If, as we explain in Question #0003, Harold was not trying a surprise attack, he would have taken the minimum number of men he thought he needed to achieve his immediate aims.

We explain in answer to Question #0005 that Harold's strategy was to negotiate the renouncement of William's claim on the English crown, probably preceded by a blockade to improve his negotiating position. There were only two egress routes for an army trying to leave the Hastings Peninsula, namely the Rochester Roman road and the isthmus ridge at Sprays Wood. The latter is barely 500m across, the former probably no more than two cart widths where it crossed the River Brede. This bridge is the also the obvious place for William and Harold to negotiate face-to-face because both would have felt safe from being ambushed. If, as we explain in Question #0001, Harold was ignorant of the huge Norman cavalry when he decided to leave London, he would have believed that he had plenty of men to blockade the Hastings Peninsula and to defend the Brede river crossing.

#2199 | 5th February 2025 | JBS

Reply

-

Why did Harold camp within striking distance of the enemy?

#0011 | 6th February 2025 | JBS

Harold clearly believed that his camp was safe from attack; otherwise he would have camped elsewhere. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle supports this by stating: "Wyllelm him com ongean on unwær, ær þis folc gefylced wære", meaning "William came against him unexpectedly, before his [Harold's] army was assembled". In other words, Harold did not expect to be attacked.

Harold would not have felt secure at either of the orthodox English camps because the Normans could trap them by blockading the Rochester Roman road. However, unaware of the Norman cavalry, as we explain in Question #0001, Harold would have felt safe anywhere near the Roman road and north of the Brede because he would have believed that he had enough men to blockade the only viable egress routes for the Norman infantry (see Question #0009). Unfortunately for Harold, the Norman cavalry could bypass blockades to outflank the English army before they could retreat back up the Roman road to safety.

#2191 | 6th February 2025 | JBS

Reply

-

Why was Harold unware of the Norman cavalry until it was too late?

#0013 | 7th February 2025

The only credible explanation for Harold's disastrous decision to enter the theatre of war and his equally bad decision to camp within striking distance of the enemy is that he was unaware of the Norman cavalry until it was too late. Wace says that Harold blames the Count of Flanders for feeding him misleading intelligence, allegedly having written to him to say that William would bring few horses. There is more to it.

Harold sent messengers into the Norman camp and scouts onto the Hastings Peninsula. According to Poitiers, William captured two of these scouts and escorted them around the Norman camp before sending them back. Yet none of these messengers and scouts could have reported seeing a significant number of Norman horses. The only plausible explanation is that the Norman cavalry were not in the camp but were thinly spread over a wide area. Poitiers says that they were out foraging on the day that Harold arrived in the theatre of war. Perhaps they were out foraging every day, and were therefore missed by Harold's messengers and scouts. Perhaps the Norman horses had to be spread over a wide area due to a lack of pasture.

Yet, this would not explain why William escorted Harold's scouts on a tour of the Norman camp or sent them back armed with this intelligence. The only likely explanation for William's actions is that he was deliberately sandbagging to conceal the strength of his cavalry for fear its discovery might spook Harold into returning to London. He therefore showed Harold's scouts around the Norman camp specifically so that they would report back to Harold that the Normans had no cavalry.

#2206 | 7th February 2025 | JBS

Reply

-

Why did Harold choose to fight when he knew that he could not win?

#0015 | 11th February 2025

Harold's decision to fight seems inscrutable. Knights and archers comprised more than a third of the Norman army. The English were almost entirely infantrymen who could only be deployed as a static shield wall. With these adversaries, the shield wall cannot win. Its best outcome is to survive, and even a minor lapse of discipline - which was almost inevitable when more than 80% of the English army were farmers - would lead to disastrous defeat. Yet the relative safety of dense woodland was less than a mile from any of the battlefield candidates, and Harold could have cantered to complete safety beyond the River Rother in 20 minutes. The only credible explanation for Harold's decision to fight is that the English were trapped. The only battlefield candidate where they could have been trapped is Hurst Lane in Sedlescombe.

#2194 | 11th February 2025

Reply

-

Why did William concentrate his attack on the best defended section of the shield wall?

#0019 | 11th February 2025 | JBS

Most of the contemporary accounts say that the battle ended late in the day following a feigned retreat that distrupted the English line. If that ruse had failed, Harold and his brothers might have used the cover of darkness to escape through the nearby Andredsweald forest. It is impossible to know whether they would have done, but William could not take that risk that they might.

William would surely have jumped at any tactic that might end the battle early. Therefore, if he was faced with an open shield wall - like the one proposed at the orthodox battlefield, Telham Hill and Caldbec Hill - it beggars belief that he did not command his cavalry to ride around the ends of the the English line to attack Harold from behind and above. Had he been offered this possibility, the battle would have been over in 15 minutes. Therefore, he was not offered this possibility, which means that the shield wall was enclosed, exactly as described by Wace, Baudri, Draco Normannicus and others. If the shield wall was enclosed the battle was not fought at the orthodox Battle Abbey or Telham Hill or Caldbec Hill. Moreover, the extreme length of the shield walls proposed at Old Heathfield and Blackhorse Hill - 2.5km and 2km respectively - mean that a battle at wither of those locations would not have taken the form described in the contemporary accounts. Therefore, the battle was fought at the only battlefield candidate where an enclosed shield wall is consistent with those descriptions, Hurst Lane in Sedlescombe.

#2196 | 11th February 2025

Reply

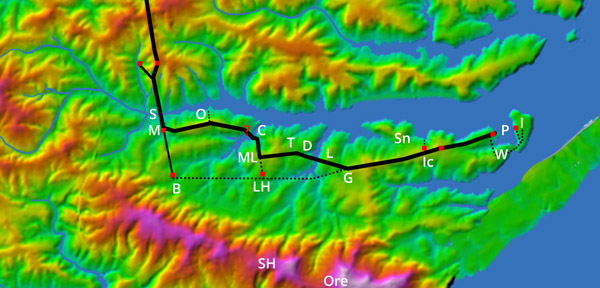

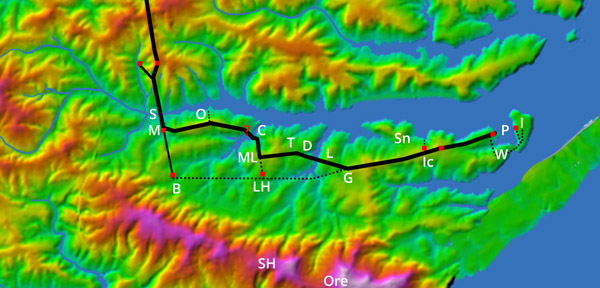

1a Twelve more reasons to believe that the Rochester Roman road terminated at modern Winchelsea

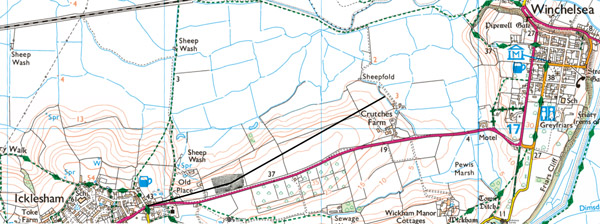

Excavated sections of Roman road marked by red dots

David Staveley Roman road geophysics at Icklesham, showing trench as a red line.

- A section of metalled Roman road was seen by William MacLean Homan at the A259 motel in modern Winchelsea (labelled I for Iham on diagram above) in the 1930s.

- A section of metalled Roman branch road was found by Voë Vahey of HAARG heading north from Old Place, Icklesham (Ic). It must have connected to a Roman trunk road and Margary 13, the Rochester Roman road, is the only one in the area.

- A section of 'made stone road' was found at Crutches Farm - between Icklesham and modern Winchelsea - by Herbert Lovegrove in 1934.

- A post-Conquest writ issued in 1294 refers to the Rochester Roman road as the 'London to Winchelsea road', another issued in 1300 refers to it as the 'Winchelsea to Robertsbridge road'.

- There is a settlement named Wickham (W) immediately adjacent to modern Winchelsea. This is the Old English name for former Roman civilian settlements known as vicus/vici which are adjacent to the access road to Roman fortifications.

- Zoe Vahey reports that a Will dated 1493 mentions repairs to 'Ikelsham Strete'. Most roads anciently named 'Street' were paved Roman roads that were still being used in Anglo-Saxon times.

- The Anglo-Saxons liked to make settlements adjacent to Roman roads, and there is a string of Anglo-Saxon settlements along the south bank of the Brede. East to west they are Iham, the Anglo-Saxon name for modern Winchelsea (I), Wickham (W), Icklesham (Ic), Snailham (Sn), Guestling (G), Lidham (L), Doleham (D), Toreham (T), Crowham (C), and Sedlescombe (S). Nowhere else in southern England has so many Anglo-Saxon settlements so close together. It seems likely that they had a common raison d'être, which in this area was probably to service traffic that passed along the Roman road.

- There is a string of Roman iron workings at the Anglo-Saxon settlements listed in 8, as well as at the major Roman industrial site at Oaklands (O). Bulky iron ore and iron blooms would have been moved on a metalled road to be processed or shipped, which in this area could only have been the Rochester Roman road or a branch off it.

- Roman concrete bridge abutments have been found crossing Forge Stream.

- There is a Roman looking zig-zag road with cuttings and causeway at Rock's Hill in Crowham (red question mark on the diagram above).

- The field surrounding Crutches Farm, through which the Roman road passes, is known as 'Road Field', and was referred to by this name in 18th century tithe maps before the modern A259 road had been constructed.

2a

Five more reasons to believe that there was a Roman fortification at modern Winchelsea

No archaeological evidence of a Roman castra has been found at modern Winchelsea, but there is no reason there should. It would have had timber walls and few if any permanent

buildings. Legionaries would have used the bathhouse and forum at nearby Beauport Park. There is, however, other evidence that there was a castra at modern Winchelsea:

1. Wickham

A manor named Wickham is located immediately adjacent to modern Winchelsea. 'Wickham' is the Old English name for

former Roman civilian settlements that were located outside the main gate of Roman fortifications.

2. Promontory

The Rochester Roman road terminated at a fortified castra somewhere east of Icklesham. The Romans liked to build permanent

castras on elevated headlands and peninsulas with a commanding view, at Pevensey and Arbeia, for example. Modern Winchelsea

is east of Icklesham and the only promontory in the Brede basin with a commanding sea view.

3. Beauport Park

Beauport Park was the third biggest iron ore mine in the Roman Empire. Nearby iron ore mines at Oaklands and Footlands were also huge by Roman standards.

They were too valuable a group of assets to leave unguarded. There must been a castra in the vicinity and modern Winchelsea was the only place in the vicinity with

suitable geography for a Roman castra.

4. Hæstingaceastre

The Aldredian burh of Hæstingaceastre was somewhere on the Hastings Peninsula. The 'ceastre' part of its name means that it was built a former Roman fortification.

Modern Winchelsea is the only place in the vicinity with suitable geography for a Roman castra.

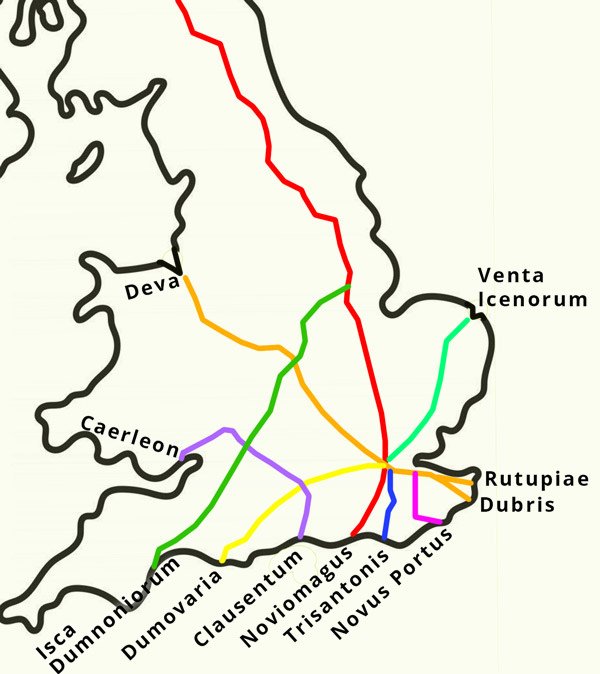

5. Novus Portus

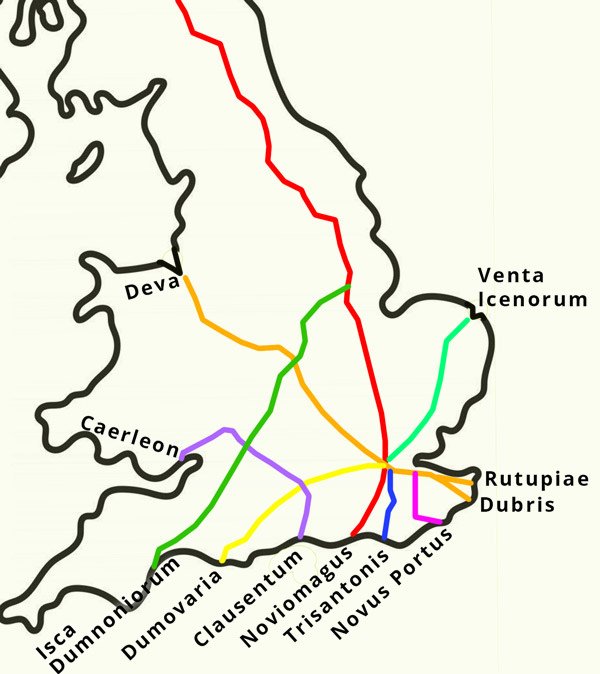

Major Roman roads in Britain and the port at which they terminated

All Roman trunk roads that reach the coast in Britain terminated at ports - see diagram above. All Roman ports were guarded by legionaries based in a nearby castra.

Where there was a promontory overlooking the port, the castra was on that prompontory. The Brede basin had 85% of the Weald's iron ore reserves. Nearly all of its

output was shipped to the Classis Britannica base in Boulogne. Bulk products like iron ore and iron blooms would not have been hauled up and over the Hastings Ridge.

They must have been shipped from a port in the Brede basin and the only likely candidate is the natural harbour adjacent to modern Winchelsea, now known as Pewis Marsh.

We believe that this port was Ptolemy's long lost port of Novus Portus, as we explain here

3a

Nine more reasoins to believe that the main Norman camp was at modern Winchelsea

There is a link between Hæstingaceastre, Hæstingaport and Hastinges:

- The Bayeux Tapestry says that the main Norman camp was at Hæstingaceastre. All the other contemporary accounts say it was at Hæstingaport or Hastinges. The only way they can all be right is if the three placenames were cognates.

- Hæstingaceastre was one of 36 'Grately Code' mints. Coins from that mint are stamped with 'HESTINGA' or with an abbreviation of 'HÆSTINGACEASTRE' or an abbreviation of 'HESTINGAPORT' as if they are cognates. It seems likely that Hæstingaceastre mint melted and restamped foreign coin and bullion taken as payment from Hæstingaport customers.

- John of Worcester refers to Hæstingaceastre, Hæstingaport and Hastinges as 'Heastinga', as of they are cognates.

- The Chronicle of Battle Abbey says that the main Norman camp was at a 'port named Hastingas', implying that Hastinges and Hæstingaport are cognates.

There are many reasons to believe that Hæstingaport was at the mouth of the Brede estuary:

- De viis Maris, written in the middle of the 12th century, specifically says that modern Hastings's port was at Old Winchelsea, at the mouth of the Brede. If it was the main port in the region a hundred years after the Conquest, it was surely the main port in the region in the middle of the 11th century.

- The Brede basin had some 70 percent of east Sussex's salt production in Anglo-Saxon times. Most of its saltpans, if not all, would have been on the Brede north bank. It is implausible that north-bank salt would have been hauled up and over the Udimore Ridge when it could have been used or shipped from a port at the mouth of the Brede.

- If there was some salt production on the south bank, it would not be hauled up and over the Hastings Ridge when it could be used or shipped from a port at the mouth of the Brede.

- The Brede basin was the only place in the region that is suitable to farm ship's timber thanks to its steep wooded banks. The timber would have been log-flumed down to the Brede and floated downstream to be used or exported from a port at the mouth of the Brede.

- The Brede basin had 85 percent of the Weald's iron ore reserves in Roman times. There is no evidence that iron ore was mined or processed in medieval times, but if it was, the Brede basin would have had the vast majority of its reserves. It is is implausible that bulk products like iron ore or iron blooms would have been hauled up and over the Hastings Ridge if it could be shipped from a port at the mouth of the Brede.

- The Brede basin was the only part of the Hastings Peninsula that was serviced by a Roman trunk road - i.e. one connected to the rest of the Roman road network - and was therefore the only Hæstingaport candidate where bulk goods could be hauled to or from the hinterland by cart.

- Rameslie manor is recorded in Domesday as the only manor on the Hastings Peninsula that had a large non-farming population and large number of burgesses, nearly always an indication of a manor that encompasses a trading port. Rameslie manor surrounded the Brede estuary, but did not encompass modern Hastings or any of the other Hæstingaport candidates. Therefore, Old Winchelsea is the only Hæstingaport candidate that is consistent with Domesday.

- Rameslie is the only manor in the region that is recorded in Anglo-Saxon Charters as having had a pre-Conquest port.

- Old Winchelsea is the only Hæstingaport candidates that was an important port after the Conquest. It was where William returned after visits to Normandy. It was where William Rufus assembled his army before his aborted invasion of Normandy. It was where Dauphin Louis took the French army when they needed to escape back to Normandy. In the early 13th century, it had ten times the trading volume of any other port between Dover and Southampton.

If Hæstingaport, Hæstingaceastre and Hastings were cognates, there is strong evidence they were at Old and modern Winchelsea, which means that the Norman camp was at modern Winchelsea.

4a

More evidence that the Battle of Hastings was not fought at the orthodox Battle Abbey location

Battle Abbey uniquely marks where the battlefield is not

- No Christian places of worship anywhere in the world have been constructed on a battlefield, with the alleged exception

of Battle Abbey. There is good reason. Medieval people were terrified of revenants, especially of being haunted by the

souls of unburied victims of violence. If Battle Abbey had been built on the battlefield, it would have been

shunned by monks, churchgoers, and pilgrims.

- Building a church on a battlefield would be widely perceived as the glorification of violence, something that

Church authorities would abhor. William would have been especially conscious of this because he commissioned

Battle Abbey as penance to earn the Pope's absolution for the violence and death he caused by the Conquest.

The Pope is unlikely to have granted absolution for what would appear to be the cynical glorification of that violence.

-

Battle Abbey's original name was 'Sancti Martini de Bello', meaning 'Saint Martin of the War', appropriate

because it was built as penance for the violence and death caused by the entire campaign, not just for that caused at the battlefield.

It is worth noting that there was relatively little death and violence at the Battle of Hastings compared to subsequrnt events, escpecially the 'Harrowing of the north'.

Latin had other words for a battle. If Battle Abbey had been built on the battlefield, it is likely to have been named 'Sancti Martini de Pugno',

'Saint Martin of the Battle', or similar.

-

Battle Abbey allegedly marks the exact location where Harold died, but it seems implausible that William have been so naive as to give Anglo-Saxons rebels

a focal point to worship Harold as a martyr.

The orthodox battlefield contradicts nearly all the geographic battlefield descriptions in the contemporary accounts

- It was not near to any immense, deep and precipitous sided pits, let alone the three different pits descibred by Poitiers,

the Chronicle of Battle Abbey, Orderic and Wace.

- It contradicts Wace's detailed description of the Norman advance.

- It was not adjacent to a lateral ditch, into which the Normans were shield charged according to Wace.

- It does not have a plain below the proposed contact zone as described by Wace.

- It is not overlooked by another hill, as described by Wace.

- It is not a small hill as described by Pseudo-Ingulf

- It is not narrow, as described by John of Worcester.

- It has no reason for the fighting to be more intense in the middle, as described by Poitiers; indeed, the slope is steepest in the middle,

so the opposite would have been more likely.

- It was not steeper than the approach at the time, as described by Carmen (although some subsequent landscaping work means that it is now)

- It is not on a spur, as described by Baudri.

- It is not on a north-south ridge or spur, as described in the Chronicle of Battle Abbey.

- It would not have been difficult to tightly encircle, as described by Poitiers.

- It is not nine Roman miles from the orthodox Norman camp, as described by John of Worcester.

- Its flight route would have been down the valley in which Marley Lane now runs, not through woodland, untrodden wastes, and land too rough to be tilled, as described by

Carmen, Poitiers, Quedam Exceptione, and Wace

- It was not adjacent to a wood in which the English camped, as described by Carmen.

- It was not visible from the Norman battle camp, as described by Brevis Relatio, Baudri, Draco Normannicus and others.

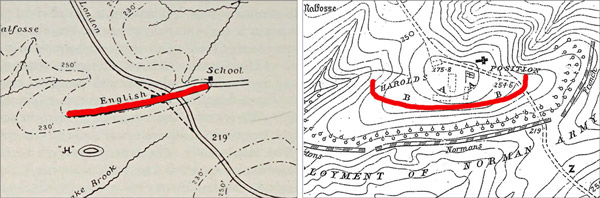

The orthodox battlefield is inconsistent with William's battle tactics

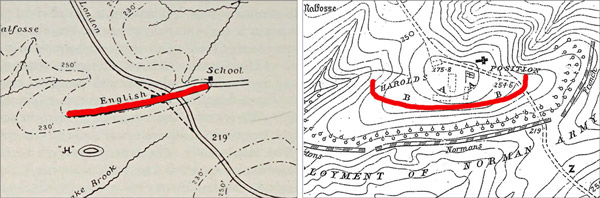

Shield walls proposed by Lieutenant-Colonel Burne (L)

and Major James (R) with our red highlighting

Every shield wall that has been proposed at the orthodox battlefield is open and straight or straightish. The two depicted on

the image above were proposed by senior soldiers. Thirty more are depicted on our blog about the evolution of the orthodox

battlefield theory, here.

Battle Abbey narrow flanking options

If William was faced with any shield wall that has been proposed for the orthodox Battle Abbey battlefield, he would have sent his cavalry around the open ends of the

English line to attack Harold from behind and above. Considering that William nearly ran out of time to achieve victory before nightfall but could have ended a battle

at the orthodox Battle Abbey battlefield location in 15 minutes by outflanking the English line, it is inconceivable that the battle was fought at the orthodox

Battle Abbey location. Moreover, Baudri says that William posted horsemen behind the English line to prevent Harold trying to escape. But if the English line was

open and there were Norman horsemen behind the English line, William would have commanded them to ride up behind Harold and lop off his head before the battle had

even started.

The orthodox battlefield is inconsistent with Harold's battle tactics

In a battle between a static shield wall faces and an enemy with a large contingent of archers and cavalry, the shield wall cannot win. Its best outcome

is to survive. But if the English army was at the orthodox Battle Abbey battlefield location and Harold's objective was to survive, he would have melted away

into nearby woodland and escaped through the Andredsweald. Harold's decision to establish a static shield wall and fight implies that the English army was

trapped which would not have been possible at the orthodox Battle Abbey battlefield.

The orthodox battlefield is inconsistent with Harold's troop deployment

Every shield wall that has been proposed at the orthodox Battle Abbey battlefield is open and straight or straightish. But Baudri specifically states and then

reiterates that the shield wall was wedge-shaped, while both Carmen and Wace (five times) imply the same. Moreover, Poitiers, Wace, Carmen, Henry of Huntingdon,

the Chronicle of Battle Abbey, Brevis Relatio and Draco Normannicus all say or imply that the shield wall was enclosed. And this makes perfect sense. It was

standard practice in Roman times for infantry to form enclosed shapes to defend against cavalry. Harold Hardrada used the tactic to defend against the English

cavalry at Stamford Bridge just two weeks before the Battle of Hastings. It is inconceivable that Harold would not have enclosed his shield wall to defend

against the Norman cavalry.

The orthodox battlefield is inconsistent with place name clues from the contemporary accounts

- The orthodox battlefield was not at or near somewhere anciently named 'Senlac', as described by Orderic Vitalis. If it was 'anciently named', the name is Old English, so it means

'sandy lake' or 'sandy loch'. This 'loch' would be in the medieval English sense of a body of water that is cut off at low tide. Neither term would apply to anywhere

near Battle, which is located on the Hastings Ridge.

- The orthodox battlefield was not at or near anywhere named Herste, as described by the Chronicle of Battle Abbey, at the time of the battle.

- Hechelande, the location of the Norman battle camp according to the Chronicle of Battle Abbey, was not between the orthodox Norman sea camp and the orthodox

battlefield at the time of the battle.

Absence of archaeological supporting evidence

No archaeological evidence of a battle has been found at the orthodox battlefield despite multiple surveys and excavations. Whilst big and valuable battle

artifacts would have been scavenged after the battle, and small iron artifacts might well have corroded to nothing, there should be evidence of smaller

copper alloy items like strap ends, brooches and pins. Moreover, no archaeological evidence has been found of Anglo-Saxon era occupation.

4b

Harold's route to the theatre of war

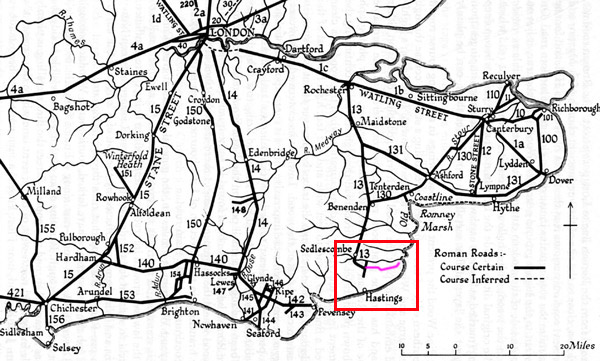

Roman roads (black lines), unpaved byways (red lines) and the Andredsweald forest (green dots)

The diagram above shows that the English army had to cross the immense Andredsweald forest to get to the theatre of war. Harold had a choice: he could either use Watling Street and the Rochester Roman road which went to the theatre of war via Rochester, or he could go through the trees on the forest floor. It seems implausible that he would have used the forest floor, but almost every historian that has written about the battle assumes he did. It needs some explanation.

One crucial point, often fogotten, is that the English army would have had a huge baggage train of ox-drawn carts and wagons. Robert Evans, logistics expert and Head of the Army Historical Branch, estimates that they would have needed 100 carts, 200 oxen, just to carry tents. Heavily laden carts and heavy animals concentrate pressure on the ground, quickly turning earthen tracks into rutted gloop. When wheel ruts sink to half the depth of a cart's wheels, the axel gets stuck and the cart would have to be lifted to start a new track. Thus, wagon train progress on any surface other than a paved road was glacially slow. For instance, Daniel Defoe mentioned that it often took a year to haul logs out of the Andredsweald.

Two other points are worth making:

- There is no reason to believe that forest tracks had been maintained since the Romans left. No Anglo-Saxon charters were issued to order their maintenance. Anglo-Saxon iron working in the Weald was rare and small scale. There were only a handful of Anglo-Saxon settlements in the forest. There was no incentive to maintain forest tracks and there were not enough inhabitants to do so anyway. Indeed, the evidence from clerical and royal itineraries indicates that wagon trains did not cross the Andredsweald on forest tracks until the 14th century when clearing was well underway. If it was too difficult to drive a few dozen royal or clerical carts through the Andredsweald on forest tracks, it is clearly implausible that Harold would try to drive hundreds of them.

- The pivotting front axel had not yet been invented, so carts and wagons could not be steered. Even though the typical spacing between tree trunks in mature deciduous forest is ten metres, it was not much more than the length of an ox-drawn cart. In the absence of forest track maintenance - see 1 above - they would regularly get jammed between trees, only to be unjammed by being first unloaded.

Given these difficulties, had the English tried to cross the Andredsweald on forest tracks, it is implausible that they could have arrived at the theatre of war in time to fight the Battle of Hastings. Even if it were not so difficult, there are several good reasons Harold would have chosen not to drive his wagon train through the Andredsweald on forest tracks:

- The role of commissariat had not yet been invented. Armies plundered food and ale (no one drank water in medieval times) as they went. They needed to plunder big farms and major settlements every day. These were commonplace near major Roman roads but absent in the Andredsweald.

- It would have been dangerous. The forest was full of hiding places. William might have posted snipers in the trees to kill Harold before he arrived at the theatre of war, as William Rufus discovered to his cost a few decades later.

Why then do historians assme that Harold did cross the Andredsweald on forest tracks? Two factors are at play.

- Historians did not know that the Rochester Roman road went to the Hastings Peninsula until Margary traced its route the 1950s. Pre-Margary historians assumed that Harold had to cross the Andredsweald on the forest floor, no matter how unlikely it seemed. They developed the orthodox narrative accordingly.

- The route of the Rochester Roman road is inconsistent with the orthodox Battle Abbey battlefield location, as we explain in the adjacent five point summary. Post-Margary historians are loath to contradict the orthodox Battle of Hastings narrative or the orthodox Battle Abbey battlefield location, so they perpetuate the forest track narrative.

5a

Eight reasons why Hurst Lane is the only viable battlefield

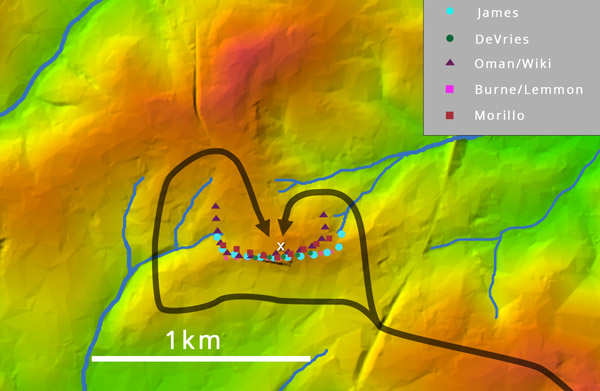

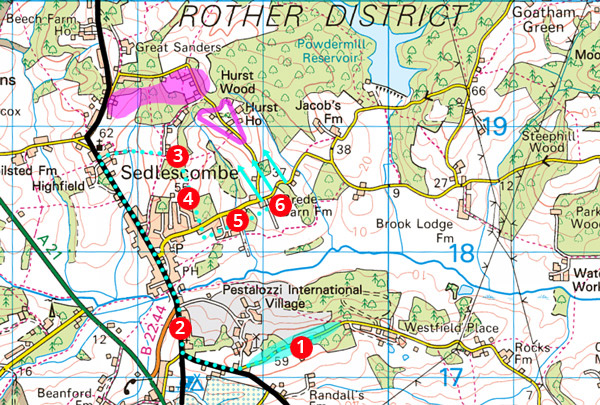

1. Wace's description of the Norman advance

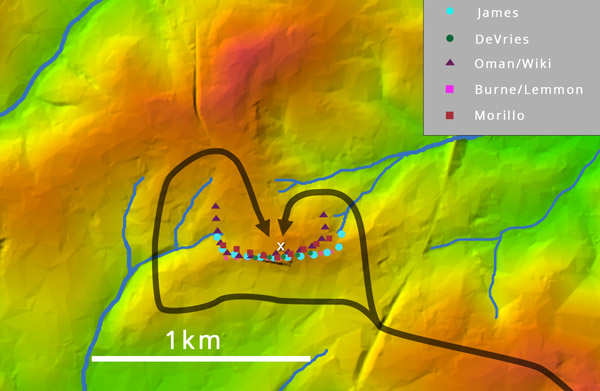

The Norman advance according to Wace, shown as a dotted cyan line

Wace provides a detailed and specific description of the Norman advance to the

battlefield from their battle camp. He explains that Harold can see the Norman battle camp from battlefield, and vice versa. As the Normans advance, they go out of Harold's sight (2)

before reappearing on the crest of a nearby hill (3). They march along the crest of that hill (4), cross a stream (5) and wheel into position

at the bottom of the battlefield hill (6). This description exactly and uniquely matches the geography at Hurst Lane.

2. Three immense pits near the battlefield through which the Engish fled

Poitiers, the Chronicle of Battle Abbey, Orderic, Wace, William of Malmesbury, Carmen and Quedam Exceptione give detailed descriptions of at least three immense

non-fluvial pits near the battlefield that featured in different phases of the English flight. The Chronicle of Battle Abbey describes the first as

immense, deep, surrounded by a rampart, precipitous-sided and 'where the fighting was going on'. It is the famous 'Malfosse' where many Norman horses and riders fell

to their death. The English make a stand at a second pit where many Normans get onto the English side before being shield charged to their death into the pit.

The English make a last stand at a third pit where Count Eustace was allegedly killed by a missile thrown across the pit from the English side.

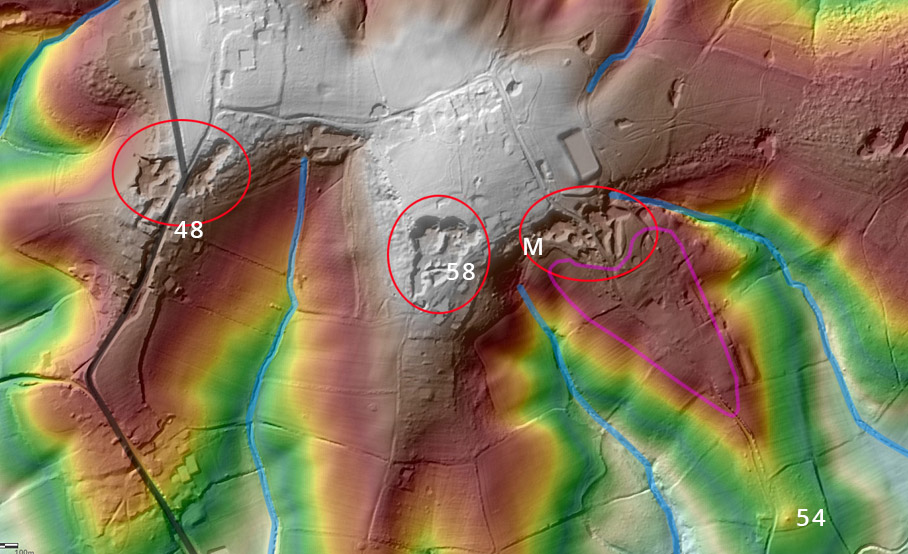

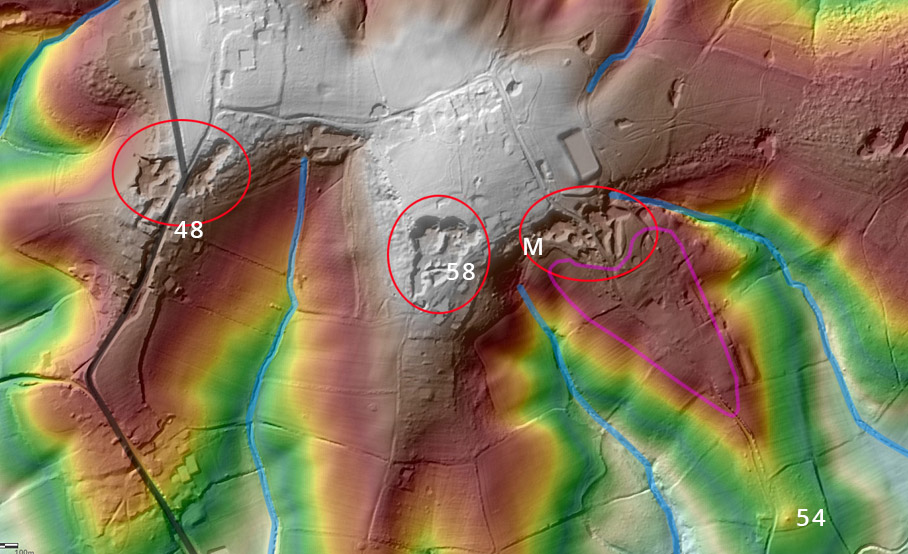

Three immense iron ore pits at the battlefield

These descriptions clearly refer to open cast iron ore mines. The LiDAR image above shows three immense deep iron ore mines at the Hurst Lane battlefield, uniquely

and almost exactly matching the twelve descriptions of immense pits in the contemporary accounts listed above. The Malfosse is labelled M. The exception is that they

are no longer surrounded by 'ramparts'. These ramparts would have been mining spoil that had been dumped around the rim of the pits. It has subsequently fallen into the

pits when the sides collapsed. The pits would have been encountered as the English fled from the battlefield - shown as a magenta heart shape - to the Rochester Roman road,

shown as a black line.

3. Contemporary archaeology

No contemporary archaeology has been found at the orthodox Battle Abbey battlefield or at any of the alternative battlefields. In the case of the accessible

western side of Hurst Lane, if there was pre-WWII archaeology, it was removed when the topsoil was redistributed to practice building aircraft landing strips before D-Day.

Elsewhere, there is no pre-indutrial revolution archaeology at the battlefield candidate or nearby. However, some very rare contemporary archaeology has been found on the route that

the English would have fled from Hurst Lane to the Rochester Roman road through Killingan Wood. This includes a Norman manufactured horseshoe, Anglo-Saxon strapends,

an Anglo-Saxon brooch, several Anglo-Saxon pins, and a tanged barbed arrowhead.

4. Impregnable upslope defence

The Normans attacked up a steep slope, yet the English were not at the top of the battlefield hill, so something prevented them attacking downslope. The only hill in the

theatre of war that was impregnable to downhill attack was Hurst Lane, where the upper side of the battlefield was protected by an immense iron ore pit.

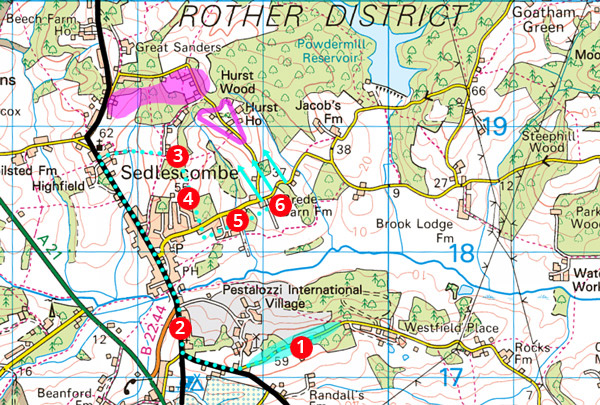

5. Herste

The Chronicle of Battle Abbey says that the battle was fought at Herste. The Domesday manor of Herste surrounded modern Hurst Lane, Hurst Wood and Hurst House, all of which

were previously spelled 'Herste'. This clue uniquely matches Hurst Lane, Sedlescombe.

6. Devil's Brook

The stream to the west of the Hurst Lane battlefield is named Devil's Brook. This is the stream into which Wace says that

one flank of the Norman army was shield charged, where more Normans died than in the rest of the battle combined. Perhaps its

name is in remembrance of this event. It is true that 'devil' is an Old English word whereas it was the Normans that

were killed, but it seems likely that the Anglo-Saxon locals avoided it for fear of wraiths and revenants.

7. Killingan Wood

The wood to the north of the Hurst Lane battlefield is named Killingan Wood. This is the wood through which the English

fled and where, according to the Chronicle of Battle Abbey, where most of them were killed. 'Killingan' derives from the Old English

word 'quillen' meaning 'to kill'. Perhaps its name is in remembrance of the lives lost within.

8. Ednoth

Herste manor appears in Domesday. It is one of only a few dozen manors in the entire country that was held by an Anglo-Saxon, namely Ednoth.

Perhaps these manors were given to Anglo-Saxons because Normans refused to farm them. It would be no surprise if Herste which would have been

considered one of the most haunted places in the country. The other battlefield candidates are either absent from Domesday or

held by a Norman.

Battlefield clues for which Hurst Lane is the only matching battlefield candidate

5b

Battlefield clues that are inconsistent with all battlefield candidates except Hurst Lane

1. Harold's decision to fight

More than a third of the Norman army was Knights and archers. The English army was entirely infantrymen. In a pre-firearm battle between infantry and cavalry,

the infantry can only be deployed as a static enclosed shield wall. The shield wall cannot win. Its best outcome is to survive, and even a minor

lapse of discipline - which was almost inevitable when more than 80% of the English army were farmers - would lead to disastrous defeat. Yet the relative safety

of dense woodland was less than two miles from any of the battlefield candidates. Harold and his brothers could have cantered to complete safety beyond the River Rother

in 20 minutes from any of the battlefield candidates. The only credible explanation for Harold's decision to fight is that the English were trapped. The only battlefield

candidate where the English could have been trapped is Hurst Lane, where the retreat could be blocked by occupying the Udimore Ridge at Cripps Corner.

2. William's failure to outflank or outmanoeuvre the English line

William had a huge cavalry, Harold had none. It is implausible that William would fail to outflank the English line if it had been deployed, as tradition

dictates for the orthodox battlefield, as a straight or straightish open line. This same issue applies to the straight or straightish open lines proposed

at Caldbec Hill and Telham Hill. Nine contemporary accounts say or imply that the English shield wall was enclosed, as would be expected for a battle

between infantry and cavalry. Accordingly, the proposed shield walls at Hurst Lane, Old Heathfield and Blackhorse Hill are enclosed. However, both the latter are

relatively long: 2.5km and 2.0km respectively. They would be no more than four ranks deep on average, probably fewer. William would clearly have used his cavalry

to probe for weaknesses all along the line, then attack using an oblique order attack at weak points. This is not the battle described in the contemporary

accounts, so it did not happen at Old Heathfield or Blackhorse Hill. Thus, William's tactics are only consistent with Hurst Lane, where he was unable

to outflank or outmanouevre the English line because it was impregnably protected on three sides by iron ore pits and lateral streams.

Battlefield geography

3. English standards visible from the Norman battle camp

Carmen explains that standards at the English camp are visible from the Norman battle camp. This is straightforward at Hurst Lane which is

less than 2km from the Norman battle camp at Cottage Lane with an unobstructed view across the Brede estuary. The view from the orthodox Norman battle camp

at Telham Hill towards the orthodox English camps at Caldbec Hill (or perhaps at Battle) is obstructed by the shoulder of Loose Farm spur. The view from Nick Austen's Norman

battle camp at Upper Wilting towards his proposed battlefield at Telham Hill and towards David Barnby's at Blackhorse Hill is obstructed by Green Street spur and

by the distance (over two miles).

4. Battlefield visible from the Norman battle camp

Baudri, Brevis Relatio, Draco Normannicus and others explain that William can see the English troop deployment from the Norman battle camp. Again, this is

straightforward at Hurst Lane where the distance to the Norman battle camp is less than a mile and the view unobstructed across the Brede estuary, but not so elsewhere.

Again, the view from Telham Hill towards Battle is obstructed by the shoulder of Loose Farm spur, the view from Upper Wilting towards Telham Hill and Blackhorse Hill is

obstructed by Green Street spur.

5. Level plain below the contact zone

Wace explains that there is a plain below the contact zone into which the English are drawn by feigned retreats and slaughtered. There is a plain 25m below the Hurst Lane

contact zone, but none at any of the other battlefield candidates.

6. The battlefield was a small hill

Pseudo-Ingulf says that Harold is killed on a small hill. Hurst Lane is just 65m elevation and 300m wide, the only one of the battlefield candidates that could be

described as a 'small hill'. By comparison, Battle Ridge is 85m elevation and 2km wide, Telham Hill is 100m elevation and 700m wide, Caldbec Hill is 105m elevation and

600m wide, Blackhorse Hill is 145m elevation and 650m wide, Hugletts Farm is 175

elevation and 700m wide.

7. The battlefield was narrow

John of Worcester says that 'the English were drawn up in a narrow place'. As we say in the point above, Hurst Lane is just 300m wide, less than half the width of the

narrowest of the other battlefield candidate and about a seventh the width of the orthodox battlefield.

8. The fighting was most intense in the middle division

Poitiers explains that William places himself and his elite Norman cavalry in the middle of three divisions where he thinks that 'the fighting will be hottest'. This would

accurately describe the geography at Hurst Lane where the flanks were less than 100m making them susceptible to being shield charged into the flanking streams. Indeed,

the flanks for the Normans that the only combat would have taken place in the middle division. The other battlefield candidates were so wide that the reverse would have

been the case: the fiercest fighting would have been on the flanks.

9. The battlefield was on the crest of a spur

Baudri states several times that the English deployment was wedge-shaped. The only likely explanation is that they were deployed on the crest of a spur. Wace states that the men of Kent

had the honour of being at the front of the English shield wall where they would be the first to engage the enemy. This is only plausible if the English deployment was

wedge-shaped or chevron-shaped, which is only likely if they were deployed on the crest of a spur. Hurst Lane is the only battlefield candidate on the crest of a spur.

10. The battlefield was on the crest of a north-south spur

The Chronicle of Battle Abbey states that the monks of Marmoutiers start to build William's penance abbey 'somewhat lower down [from the part of the batlefield hill where the

fighting took place], on the western side of the hill'. It goes on to explain that William instructed them to abandon that work and to build his abbey where it now stands.

It says that the chosen spot is where Harold died, but that statement is untrustworthy for many reasons we address in the 'Traditional battlefield' of our book. The point is

that the battlefield was near the top of a hill. It would be pointless to say that the aborted abbey is 'lower down' unless it is trying to say that it was 'lower down the crest

of the spur or ridge'. Hurst Lane is the only battlefield candidate whre this statement makes sense.

11. The English line was difficult to tightly encircle

Poitiers says that the English line was difficult to encircle, even late in the day. He is trying to say that it was tactically impractical to tightly encircle, thereby allowing

the Normans to stretch the defence and implement 'oblique order attacks' at the relative weak points. Hurst Lane is the only battlefield candidate where this would apply.

The upper slope side of the English shield wall was impregnable, protected by the vertical wall of a deep iron ore mine. The flanks were susceptible to being shield charged

into one of the flanking streams. Indeed, Wace says that this happened early in the battle, and that more Normans died in this shield charge than in the rest of the battle combined.

There is no reason that the proposed shield walls at the other battlefield candidates could not be tightly encircled. It is true that there were relatively steep slopes to

the north of the orthodox battlefield, to the east of Telham Hill, to the west of Blackhorse Hill, but the streams at the bottom of those slopes were 200m or more from the contact points.

It would not have been possible for the English to shield charge the Normans 200m, so the Normans would not have feared venturing onto these slopes.

12. Bayeux Tapestry scenes 48, 54 and 58

Bayeux Tapestry scene 48

Bayeux Tapestry scene 48 shows William standing outside a Romanesque church during the Norman advance from their battle camp to the battlefield. Romanesque

churches were extraordinarily rare in Anglo-Saxon England. The only likely Romanesque church in the theatre of war would have belonged to the

Norman Abbey of Fécamps which had been gifted the manors of Rameslie and Brede by King Cnut. The most likely location for this church would have been

adjacent to the Rochester Roman road, where it could collect taxes from passing freight carriers. Beryl Lucey stated that there was an Anglo-Saxon era

church on the site now occupied by the Norman church of St John the Baptist, Sedlescombe. That church would have been in the right vicinity to have been

the church depicted in scene 48. We have marked it 48 on the LiDAR image above.

Bayeux Tapestry scene 54

Bayeux Tapestry scene 54 shows the English troops fighting back-to-back on top of a narrow hill. It exactly matches the view of our proposed Hurst Lane battlefield

as seen from the knoll labelled 54 on the LiDAR image above.

Bayeux Tapestry scene 58

Bayeux Tapestry scene 58, the last scene on the Tapestry, shows the English fleeing after the battle. It seems to be a weird double decker scene that has defied

understanding hitherto. However, uniquely, it exactly matches the view looking north from the south rim of the middle iron ore pit, labelled 58 on the LiDAR above,

with the English fleeing along the rim of the pit and across the bottom of the pit.

13. Senlac

Orderic Vitalis repeatedly says that the battlefield was at a place 'anciently known as Senlac'. 'Anciently known' implies that Senlac is

an Old English name, which therefore means 'sandy lake' or 'sandy loch'. In medieval England, a 'loch' usually referred to a stretch of

intertidal water cut off at low tide. In medieval times, there was a low-tide ford south of Brede village, so the Brede estuary between

Sedlescombe and Brede village was both a loch and a lake. It sat between the Norman battle camp at Cottage Lane and the battlefield at

Hurst Lane. The term is inconsistent with all the other battlefield candidates, none of which were near a tidal river.

14. The battlefield has an adjacent fluvial ditch into which the Normans were shield charged

Supporters of every battlefield candidate propose a nearby ditch as the Malfosse. They are all fluvial valleys, and therefore not the Malfosse because it was a non-fluvial pit.

However, in principle, they could be Wace's shield charge ditch. The devil is in the detail. The valley needs to be parallel to the battlefield because Wace says that the Normans

pass it without noticing on their advance. The stream at the valley bottom valley must be near enough for a shield charge, and not through woodland. Oakwood Ghyll, the traditional

Malfosse is over a kilometer from the orthodox Battle Abbey battlefield and therefore too far to be shield charged. It is 300m from the Caldbec Hill battlefield candidate,

too far we think for a shield charge. Hunter's Ghyll is only 50m from Austin's proposed east flank, but Austin's engagement theory is based on it being impenetrable woodland.

He cannot have it both ways: either it is impenetrable woodland, in which case the Normans could not be shield charged through it, or it is not impenetrable woodland, in which

case the battle did not happen on Telham Hill. The Rackwell Stream west of Barnby's Blackhorse Hill battlefield is 200m from the contact zone, a long way to be shield charged.

The Bingletts Wood stream is 400m from the Old Heathfield battlefield candidate, too far to be shield charged. Devil's Brook is just 120m from the Hurst Lane battlefield

contact zone and immediately behind the Norman left flank. If the Normans left a 40m gap to avoid being hit by missiles, Devil's Brook would have been just 30m behind their

last rank, easily within shield charge range.

Some more battlefield location clues

5c

Some more battlefield location clues

1. The battlefield was overlooked by another hill

Wace explains that the youths and clerics watch the battle from an adjacent hill. This would have been straightforward at Hurst Lane because it is overlooked by the adjacent

Churchlands Lane spur which is treeless and 10m higher. The orthodox battlefield is overlooked by a hill at what used to be Down Barn Farm, west of Loose Farm. Caldbec Hill

and Hugletts Farm are the highest hill in their vicinity, and therefore are not overlooked. Austin's Telham Hill battlefield and Barmby's Blackhorse Hill battlefield are

both overlooked by the Hastings Ridge, and they are only separated by one kilometre. If there were no trees on the Ridge or surrounding the battlefield, a spectator could

see the action from the Ridge or from the other battlefield candidate. However, both engagement theories rely on the battlefield being surrounded by impenetrable woodland,

in which case neither would be visible from a nearby hill.

2. The battlefield was nine Roman miles (eight imperial miles) from the main Norman camp

This apparently specific clue from John of Worcester is not as useful as it seems because he is unclear about whether he means crow flying miles or marching miles.

Hurst Lane is the only battlefield candidate that exactly matches this clue, being eight imperial marching and crow flying miles from our proposed Norman camp at

modern Winchelsea. It clearly contradicts Telham Hill and Blackhorse Hill, both of which are less than two miles from their proposed Norman camp at Upper Wilting.

It clearly contradicts Old Heathfield which is seventeen crow flying miles from the orthodox Norman camp at modern Hastings. The orthodox battlefield at Battle

Abbey and the Caldbec Hill battlefield candidate are just shy of eight marching miles from the orthodox Norman camp at modern Hastings, although considerably

less crow flying miles.

3. The battlefield is steeper than the approach

Carmen says that William can see Harold over the heads of the shield wall. This can only mean that the battlefield is steeper than the approach. This is clearly the case at

Hurst Lane, where there is a level plain just below the contact zone and a relatively shallow approach to it from the river. The orthodox battlefield contact zone is steeper

than the approach, but the ground has been relandscaped since the battle so it is difficult to know what it was like at the time. The slope at Telham Hill is consistent,

so it is not steeper than the approach. The opposite applies at Blackhorse Hill and Caldbec Hill where the proposed shield wall is at the inflection point where a

relatively flat hilltop breaks into a relatively steep slope, the exact opposite of what Carmen describes.

4. The English camp is in woodland immediately beyond the battlefield

Carmen explains that Normans see the English emerge onto the battlefield from the wood in which they camped. This exactly describes Hurst Lane

which backs onto Killingan Wood where we propose the English camped. Alas, the description is not specific enough to be sure about some of the other canidates.

We assume that Carmen means that barons at the Norman battle camp saw the English emerge from the wood, which would narrow the possibilities because very few

battlefield candidates were visible from their proposed battle camp, but Carmen does not say so explicitly. A broader interpretation, meaning that the English emerged

from any wood, makes it consistent with Telham Hill and Blackhorse Hill, both of which back onto the Hastings Ridge which would have been lined with woodland.

Even this broad interpretation is inconsistent with Caldbec Hill and Old Heathfield, both of which are supposed to have been on unwooded hilltops.

5. The English flight was along roads, through woodland and through untrodden wastes

These descriptions are culled from Carmen, Poitiers, Quedam Exceptionne and Wace. The only battlefield candidate that matches all of them is Hurst Lane which

backed onto Killingan Wood, which was surrounded by a moonscape of iron ore pits and spoil hills, and which was just a few hundred metres from the Rochester

Roman road. All the other battlefield candidates would have been near woodland. All the other battlefield candidates might have been near ridgeway byways, although

it is a stretch to think that this is what Poiters and Wace are referring to. And it is difficult to know what Poitiers meant by 'untrodden wastes'.

6. The battlefield was roughly an hour's march from the Norman battle camp

Many contemporary accounts state that the battle started at the third hour of the day. Allowing time for Mass, breakfast, the ride from the Norman sea camp to

the battle camp, getting dressed into armour and listening to William's pep talk, there would have been no more than an hour for the Normans to get from their

battle camp to the foot of the battlfield hill. This is consistent with the two kilometer march from our proposed Norman battle camp at Cottage Lane to Brede Lane

on the route described by Wace. It could be consistent with Telham Hill and Blackhorse Hill if there was a road across the intervening marshland, although there is

no evidence of such a road. It could be consistent with Old Heathfield if the Norman battle camp was where Welchman and Coleman propose at Dallington.

David Staveley Roman road geophysics at Icklesham, showing trench as a red line.

David Staveley Roman road geophysics at Icklesham, showing trench as a red line.

I have always thought that Battle Abbey is too flat for the battlefield. This is the first alternative battlefield theory I have seen that looks plausible. Keep up the good work!